Mood:

Topic: Simplicity

by Roman Krznaric This article is based on his book, How Should We Live? Great Ideas from the Past for Everyday Life

What might history teach us about living more simple, less consumerist lifestyles?

The ancient Greek philosopher Diogenes took simple living to the extreme, and lived in an old wine barrel. Painting by Jean-Léon Gérôme, used courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

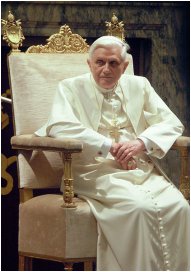

When the recently elected Pope Francis assumed office, he shocked his minders by turning his back on a luxury Vatican palace and opting instead to live in a small guest house. He has also become known for taking the bus rather than riding in the papal limousine.

The Argentinian pontiff is not alone in seeing the virtues of a simpler, less materialistic approach to the art of living. In fact, simple living is undergoing a contemporary revival, in part due to the ongoing recession forcing so many families to tighten their belts, but also because working hours are on the rise and job dissatisfaction has hit record levels, prompting a search for less cluttered, less stressful, and more time-abundant living.

At the same time, an avalanche of studies, including ones by Nobel Prize-winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman, have shown that as our income and consumption rises, our levels of happiness don't keep pace. Buying expensive new clothes or a fancy car might give us a short-term pleasure boost, but just doesn't add much to most people's happiness in the long term. It's no wonder there are so many people searching for new kinds of personal fulfillment that don't involve a trip to the shopping mall or online retailers.

If we want to wean ourselves off consumer culture and learn to practice simple living, where might we find inspiration? Typically people look to the classic literature that has emerged since the 1970s, such as E.F. Schumacher's book Small is Beautiful, which argued that we should aim "to obtain the maximum of wellbeing with the minimum of consumption." Or they might pick up Duane Elgin's Voluntary Simplicity or Joe Dominguez and Vicki Robin's Your Money or Your Life.

I'm a fan of all these books. But many people don't realize that simple living is a tradition that dates back almost three thousand years, and has emerged as a philosophy of life in almost every civilization.

What might we learn from the great masters of simple living from the past for rethinking our lives today?

Eccentric philosophers and religious radicals

Anthropologists have long noticed that simple living comes naturally in many hunter-gatherer societies. In one famous study, Marshall Sahlins pointed out that aboriginal people in Northern Australia and the !Kung people of Botswana typically worked only three to five hours a day. Sahlins wrote that "rather than a continuous travail, the food quest is intermittent, leisure abundant, and there is a greater amount of sleep in the daytime per capita per year than in any other condition of society." These people were, he argued, the "original affluent society."

In the Western tradition of simple living, the place to begin is in ancient Greece, around 500 years before the birth of Christ. Socrates believed that money corrupted our minds and morals, and that we should seek lives of material moderation rather than dousing ourselves with perfume or reclining in the company of courtesans. When the shoeless sage was asked about his frugal lifestyle, he replied that he loved visiting the market "to go and see all the things I am happy without." The philosopher Diogenes—son of a wealthy banker—held similar views, living off alms and making his home in an old wine barrel.

We shouldn't forget Jesus himself who, like Guatama Buddha, continually warned against the "deceitfulness of riches." Devout early Christians soon decided that the fastest route to heaven was imitating his simple life. Many followed the example of St. Anthony, who in the third century gave away his family estate and headed out into the Egyptian desert where he lived for decades as a hermit.

Later, in the thirteenth century, St. Francis took up the simple living baton. "Give me the gift of sublime poverty," he declared, and asked his followers to abandon all their possessions and live by begging.

Simplicity arrives in colonial America

Simple living started getting seriously radical in the United States in the early colonial period. Among the most prominent exponents were the Quakers—a Protestant group officially known as the Religious Society of Friends—who began settling in the Delaware Valley in the seventeenth century. They were adherents of what they called "plainness" and were easy to spot, wearing unadorned dark clothes without pockets, buckles, lace or embroidery. As well as being pacifists and social activists, they believed that wealth and material possessions were a distraction from developing a personal relationship with God.

But the Quakers faced a problem. With growing material abundance in the new land of plenty, many couldn't help developing an addiction to luxury living. The Quaker statesman William Penn, for instance, owned a grand home with formal gardens and thoroughbred horses, which was staffed by five gardeners, 20 slaves, and a French vineyard manager.

Partly as a reaction to people like Penn, in the 1740s a group of Quakers led a movement to return to their faith's spiritual and ethical roots. Their leader was an obscure farmer's son who has been described by one historian as "the noblest exemplar of simple living ever produced in America." His name? John Woolman.

Woolman is now largely forgotten, but in his own time he was a powerful force who did far more than wear plain, undyed clothes. After setting himself up as a cloth merchant in 1743 to gain a subsistence living, he soon had a dilemma: his business was much too successful. He felt he was making too much money at other people's expense.

In a move not likely to be recommended at Harvard Business School, he decided to reduce his profits by persuading his customers to buy fewer and cheaper items. But that didn't work. So to further reduce his income, he abandoned retailing altogether and switched to tailoring and tending an apple orchard.

Woolman also vigorously campaigned against slavery. On his travels, whenever receiving hospitality from a slave owner, he insisted on paying the slaves directly in silver for the comforts he enjoyed during his visit. Slavery, said Woolman, was motivated by the "the love of ease and gain," and no luxuries could exist without others having to suffer to create them.

The birth of utopian living

Nineteenth-century America witnessed a flowering of utopian experiments in simple living. Many had socialist roots, such as the short-lived community at New Harmony in Indiana, established in 1825 by Robert Owen, a Welsh social reformer and founder of the British cooperative movement.

In the 1840s, the naturalist Henry David Thoreau took a more individualist approach to simple living, famously spending two years in his self-built cabin at Walden Pond, where he attempted to grow most of his own food and live in isolated self-sufficiency (though by his own admission, he regularly walked a mile to nearby Concord to hear the local gossip, grab some snacks, and read the papers). It was Thoreau who gave us the iconic statement of simple living: "A man is rich in proportion to the number of things which he can afford to let alone." For him, richness came from having the free time to commune with nature, read, and write.

Simple living was also in full swing across the Atlantic. In nineteenth-century Paris, bohemian painters and writers like Henri Murger—author of the autobiographical novel that was the basis for Puccini's opera La Bohème—valued artistic freedom over a sensible and steady job, living off cheap coffee and conversation while their stomachs growled with hunger.

Redefining luxury for the twenty-first century

What all the simple livers of the past had in common was a desire to subordinate their material desires to some other ideal—whether based on ethics, religion, politics or art. They believed that embracing a life goal other than money could lead to a more meaningful and fulfilling existence.

Woolman, for instance, "simplified his life in order to enjoy the luxury of doing good," according to one of his biographers. For Woolman, luxury was not sleeping on a soft mattress but having the time and energy to work for social change, through efforts such as the struggle against slavery.

Simple living is not about abandoning luxury, but discovering it in new places. These masters of simplicity are not just telling us to be more frugal, but suggesting that we expand the spaces in our lives where satisfaction does not depend on money. Imagine drawing a picture of all those things that make your life fulfilling, purposeful, and pleasurable. It might include friendships, family relationships, being in love, the best parts of your job, visiting museums, political activism, crafting, playing sports, volunteering, and people watching.

There is a good chance that most of these cost very little or nothing. We don't need to do much damage to our bank balance to enjoy intimate friendships, uncontrollable laughter, dedication to causes or quiet time with ourselves.

As the humorist Art Buchwald put it, "The best things in life aren't things." The overriding lesson from Thoreau, Woolman, and other simple livers of the past is that we should aim, year on year, to enlarge these areas of free and simple living on the map of our lives. That is how we will find the luxuries that constitute our hidden wealth.

Source - dailygood.org