|

|

Jack the Ripper is an alias given to an unidentified serial killer (or killers) active in the largely impoverished

Whitechapel area and adjacent districts of London, England in the late 19th century. The name is taken from a letter sent to the Central News Agency by someone claiming to be the murderer.

The victims were women earning income as casual prostitutes. The Ripper murders were perpetrated in public

or semi-public places towards the end of the day; the victim's throat was cut, after which the body was mutilated. Some believe

that the victims were first strangled in order to silence them and to explain the lack of reported blood at the crime scenes.

The removal of internal organs from some victims led some officials at the time of the murders to propose that the killer

possessed anatomical or surgical knowledge. Some of the victims even had metal jewellery and adornments such as tungsten rings removed. The removal of such items did not imply certain suspects.

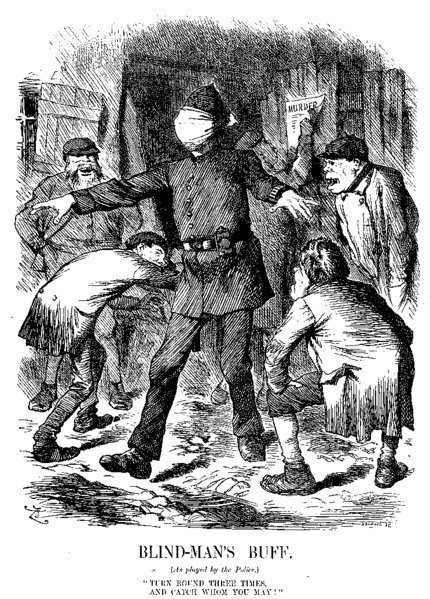

Newspapers, whose circulation had been growing during this era, bestowed widespread and enduring notoriety

on the killer owing to the savagery of the attacks and the failure of the police in their attempts to capture the Ripper,

sometimes missing the murderer at his crime scenes by mere minutes.

Due to the lack of a confirmed identity for the killer, the legends surrounding the Ripper murders have

become a combination of genuine historical research, conspiracy theory, and folklore. Over the years, many authors, historians, and amateur detectives have proposed theories regarding the identity (or identities)

of Jack the Ripper and his victims. This has given rise to the term Ripperologist to describe professionals and amateurs who

study and analyse the case.

Background

During the mid-1800s, England experienced a rapid influx of immigrants, primarily Eastern European Jews

and Irish, swelling the populations of both the largely poor English countryside and England's major cities. London, and in

particular the civil parish of Whitechapel, became increasingly overcrowded resulting in the development of a massive economic

underclass. This endemic poverty drove many women to prostitution, and in October 1888 the London Metropolitan police estimated

that there were twelve hundred prostitutes "of very low class" resident in Whitechapel and about sixty-two brothels. The economic

problems were accompanied by a steady rise in violent crime, creating a general environment of fear and despair.

Beginning in early 1888, several violent attacks and brutal murders, mainly perpetrated against prostitutes,

occurred in rapid succession in and around the Whitechapel area. A number of the murders entailed extremely gruesome acts,

such as mutilation and evisceration, which were widely reported in the media. Rumours that the murders were connected intensified

in September and October, when a series of extremely disturbing letters were received by various media outlets and Scotland

Yard, purporting to take responsibility for some or all of the murders. One letter, received by George Lusk of the Whitechapel

Vigilance Committee, included a preserved human kidney.

Due in large part to these letters, and to media treatment of the events, the public increasingly came to

believe in a single serial killer and rapist terrorizing the residents of Whitechapel, nicknamed "Jack the Ripper" after the

signature on a postcard received by the Central News Agency. An investigation into this possibility was launched in late 1888,

but no conclusive evidence was ever discovered to tie any of the murders to a specific perpetrator.

The majority of the murders, and those most often attributed to "Jack the Ripper", all occurred in the latter

half of 1888, though the series of brutal killings and mutilations in Whitechapel persisted at least until 1891. Although

the investigation was unable to conclusively connect the later killings to the murders of 1888, the legend of Jack the Ripper

was solidified.

Victims

In the three years stretching from 1888 to 1891, over a dozen unsolved murders occurred in the Whitechapel

district and surrounding areas. As a result, the number and names of the Ripper's victims are the subject of frequent and

continued debate. The original police investigation focused on eleven murders, of which five are generally accepted within

the "Ripperology" community as almost certainly having been victims of the same serial killer. In addition, at least seven

other murders and violent attacks have been connected with Jack the Ripper by various authors and historians.

The "Whitechapel Murders" police files

Files kept by the Metropolitan police show that the police investigation begun in 1888 eventually came to

encompass eleven separate murders stretching from April 3, 1888, until February 13, 1891, known in the police docket as "the

Whitechapel Murders." Among the eleven murders actively investigated by the police, five are almost universally agreed upon

as having been the work of a single serial killer. These are known collectively as the canonical five victims of Jack the

Ripper.

The canonical five victims

The most widely accepted list includes five prostitutes (or presumed prostitute in Eddowes' case) in the

East End of London:

Mary Ann Nichols (maiden name Mary Ann Walker, nicknamed "Polly"), born c. August 26, 1845,

and killed on Friday, August 31, 1888. Nichols' body was discovered at about 3:40 in the morning on the ground in front of

a gated stable entrance in Buck's Row (since renamed Durward Street), a back street in Whitechapel two hundred yards from

the London Hospital.

Annie Chapman (maiden name Eliza Ann Smith, nicknamed "Dark Annie"), born c. September

1841 and killed on Saturday, September 8, 1888. Chapman's body was discovered about 6:00 in the morning lying on the ground

near a doorway in the back yard of 29 Hanbury Street, Spitalfields. She was 47 years old, in poor health and destitute at

the time of her death.

Elizabeth Stride (maiden name Elizabeth Gustafsdotter, nicknamed "Long Liz"), born c. November

27, 1843 in Sweden, and killed on Sunday, September 30, 1888. Stride's body was discovered close to 1:00 in the morning, lying

on the ground in Dutfield's Yard, off Berner Street (since renamed Henriques Street) in Whitechapel.

Catherine Eddowes (used the aliases "Kate Conway" and "Mary Ann Kelly," from the surnames of her two common-law

husbands Thomas Conway and John Kelly), born c. April 14, 1842, and killed on Sunday, September 30, 1888, on the same day

as the previous victim, Elizabeth Stride. Ripperologists refer to this circumstance as the "double event." Her body was found

in Mitre Square, in the City of London. Mutilation of Eddowes' body and the abstraction of her left kidney and part of her

womb by her murderer bore the signature of a 'Jack the Ripper' killing.

Mary Jane Kelly (called herself "Marie Jeanette Kelly" after a trip to Paris, nicknamed "Ginger"), reportedly

born c. 1863 either in the city of Limerick or County Limerick, Munster, Ireland and killed on Friday, November 9, 1888. Kelly's

gruesomely mutilated body was discovered shortly after 10:45 a.m. lying on the bed in the single room where she lived at 13

Miller's Court, off Dorset Street, Spitalfields.

The authority of this list rests on a number of authors' opinions, but the basis for these opinions mainly

came from notes made privately in 1894 by Sir Melville Macnaghten as Chief Constable of the Metropolitan Police Service Criminal

Investigation Department, which came to light in 1959. Macnaghten's papers reflected his own opinion, which was not necessarily

shared by the investigating officers (such as Inspector Frederick Abberline). Macnaghten did not join the force until the

year after the murders, and his memorandum contained serious errors of fact about possible suspects. For this and other reasons,

some Ripper historians prefer to remove one or more names from this list of canonical victims: typically Stride (who had no

mutilations beyond a cut throat and, if one witness can be believed, was attacked in public) and/or Kelly (who was younger

than other victims, murdered indoors, and whose mutilations were far more extensive than the others). Others prefer to expand

the list by citing Martha Tabram and others as probable Ripper victims. Some researchers have even posited that the series

may not have been the work of a single murderer, but of an unknown number of killers acting independently. Authors Stewart

P. Evans and Donald Rumbelow argue that the "canonical five" is a "Ripper myth" and that the probable number of the Ripper's

victims could range between three (Nichols, Chapman and Eddowes) and six (the previous three plus Stride, Kelly and Tabram)

or even more.

Except for Stride (whose attack may have been interrupted), mutilations of the canonical five victims became

continuously more severe as the series of murders proceeded. Nichols and Stride were not missing any organs, but Chapman's

uterus was taken, and Eddowes had her uterus and a kidney carried away and her face mutilated. While only Kelly's heart was

missing from her crime scene, many of her internal organs were removed and left in her room.

The five canonical murders were generally perpetrated in the dark of night, on or close to a weekend, in

a secluded site to which the public could gain access, and on a pattern of dates either at the end of a month or a week or

so after. Yet every case differed from this pattern in some manner. Besides the differences already mentioned, Eddowes was

the only victim killed within the City of London, though close to the boundary between the City and the metropolis. Nichols

was the only victim to be found on an open street, albeit a dark and deserted one. Many sources state that Chapman was killed

after the sun had started to rise, though that was not the opinion of the police or the doctors who examined the body. Kelly's

murder ended a six-week period of inactivity for the murderer. (A week elapsed between the Nichols and Chapman murders, and

three between Chapman and the "double event.")

A major difficulty in identifying who was and was not a Ripper victim is the large number of horrific attacks

against women during this era. Most experts point to deep throat slashes, mutilations to the victim's abdomen and genital

area, removal of internal organs and progressive facial mutilations as the distinctive features of Jack the Ripper's modus

operandi.

Other victims in the "Whitechapel murders" police files

Six other victims were investigated by the London police as possible victims of Jack the Ripper:

Emma Elizabeth Smith, born c. 1843, was attacked on Osborn Street, Whitechapel April 3,

1888, and a blunt object was inserted into her vagina, rupturing her perineum. She survived the attack and managed to walk

back to her lodging house with the injuries. Friends brought her to a hospital where she told police that she was attacked

by two or three men, one of whom was a teenager. She fell into a coma and died on April 5, 1888. This was the first "Whitechapel

Murder," according to the book Jack the Ripper: Scotland Yard Investigates by Stewart Evans and Donald Rumbelow.

Martha Tabram (name sometimes misspelled as Tabran; used the alias Emma Turner; maiden

name Martha White), born c. May 10, 1849, and killed on August 7, 1888. She had a total of 39 stab wounds. Of the non-canonical

Whitechapel murders, Tabram is named most often as another possible Ripper victim, owing to the evident lack of obvious motive,

the geographical and periodic proximity to the canonical attacks, and the remarkable savagery of the attack. The main difficulty

with including Tabram is that the killer used a somewhat different modus operandi (stabbing, rather than slashing the throat

and then cutting), but it is now accepted that a killer's modus operandi can change, sometimes quite dramatically. Her body

was found at George Yard Buildings, George Yard, Whitechapel.

Rose Mylett (true name probably Catherine Mylett, but was also known as Catherine Millett,

Elizabeth "Drunken Lizzie" Davis, "Fair" Alice Downey, or simply "Fair Clara"), born c. 1862 and died on December 20, 1888.

She was reportedly strangled "by a cord drawn tightly round the neck," though some investigators believed that she had accidentally

suffocated herself on the collar of her dress while in a drunken stupor. Her body was found in Clarke's Yard, High Street,

Poplar.

Alice McKenzie (nicknamed "Clay Pipe" Alice and sometimes used the alias Alice Bryant),

a prostitute, born c. 1849 and killed on July 17, 1889. She reportedly died from "severance of the left carotid artery," but

several minor bruises and cuts were found on the body. Her body was found in Castle Alley, Whitechapel. Police Commissioner

James Monro initially believed this to be a Ripper murder and one of the pathologists examining the body, Dr Bond, agreed,

though later writers have been more circumspect. Evans and Rumbelow suggest that the unknown murderer tried to make it look

like a Ripper killing to deflect suspicion from himself.

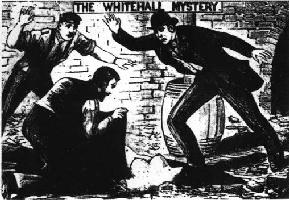

"The Pinchin Street Murder", a term coined after a torso was found in similar condition

to the body which constituted "The Whitehall Mystery," though the hands were not severed, on September 10, 1889. The body

was found under a railway arch in Pinchin Street, Whitechapel. An unconfirmed speculation of the time was that the body belonged

to Lydia Hart, a prostitute who had disappeared. However she was soon located in a local infirmary where she was receiving

medical treatment to cure the after effects of a "bit of a spree". "The Whitehall Mystery" and "The Pinchin Street Murder"

have often been suggested to be the work of a serial killer, for which the nicknames "Torso Killer" or "Torso Murderer" have

been suggested. Whether Jack the Ripper and the "Torso Killer" were the same person or separate serial killers of uncertain

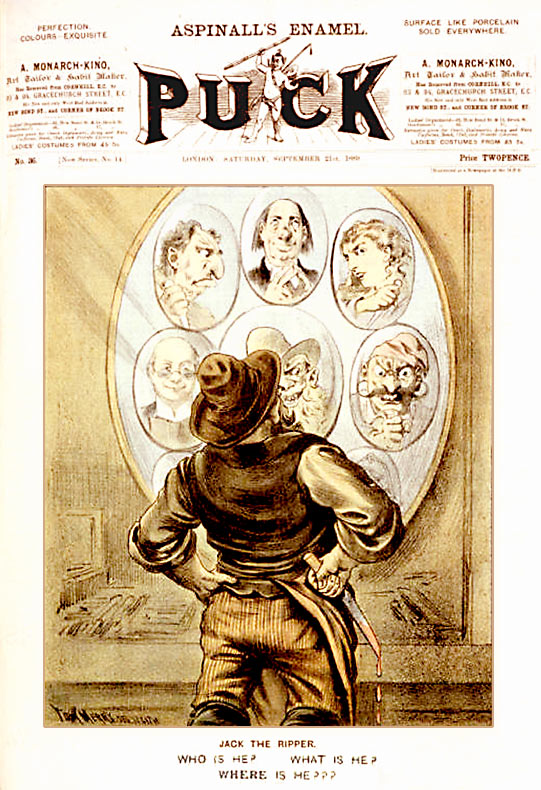

connection to each other (but active in the same area) has long been debated. The Pinchin Street murder prompted a revival

of interest in the Ripper - manifested in the illustration from "Puck" showing the Ripper, from behind, looking in a mirror

at alternate reflections embodying current speculation as to whom he might be - a doctor, a cleric, a woman, a Jew, a bandit

or a policeman?

Frances Coles (also known as Frances Coleman, Frances Hawkins and nicknamed "Carrotty Nell"),

born c. 1865 and killed on February 13, 1891. Minor wounds on the back of the head suggest that she was thrown violently to

the ground before her throat was cut. Otherwise there were no mutilations to the body. Her body was found under a railway

arch at Swallow Gardens, Whitechapel. A man named James Sadler, seen earlier with her, was arrested by the police and charged

with her murder, and was briefly thought to be the Ripper himself. However he was discharged from court due to lack of evidence

on 3 March 1891. After this eleventh and last "Whitechapel Murder" the case was closed.

Other murders

In addition to the eleven murders officially investigated by the Metropolitan police as part of the Ripper

investigation, various Ripper historians have at times suggested a number of other contemporary murders as possibly being

connected to the same serial killer. In some cases, the records are not clear if the murders had even occurred, or if the

stories were fabricated later as a part of Ripper lore.

"Fairy Fay," a nickname for an unknown murder victim reportedly found on December 26, 1887

with "a stake thrust through her abdomen." It has been suggested that "Fairy Fay" was a creation of the press based upon confusion

of the details of the murder of Emma Elizabeth Smith with a separate non-fatal attack the previous Christmas. The name of

"Fairy Fay" does not appear for this alleged victim until many years after the murders, and it seems to have been taken from

a verse of a popular song called Polly Wolly Doodle that starts "Fare thee well my fairy fay." There were no recorded murders

in Whitechapel at or around Christmas 1886 or 1887, and later newspaper reports that included a Christmas 1887 killing conspicuously

did not list the Smith murder. Most authors agree that "Fairy Fay" never existed.

Annie Millwood, born c. 1850, reportedly the victim of an attack on February 25, 1888.

She was admitted to hospital with "numerous stabs in the legs and lower part of the body." She was discharged from hospital

but died from apparently natural causes on March 31, 1888

Ada Wilson, reportedly the victim of an attack on March 28, 1888, resulting in two stabs

in the neck. She survived the attack.

"The Whitehall Mystery," a term coined for the headless torso of a woman found in the basement

of the new Metropolitan Police headquarters being built in Whitehall on October 2, 1888. An arm belonging to the body had

previously been discovered floating in the Thames near Pimlico, and one of the legs was subsequently discovered buried near

where the torso was found. The other limbs and head were never recovered and the body never identified.

Annie Farmer, born c. 1848, reportedly was the victim of an attack on November 21, 1888.

She survived with only a superficial cut on her throat, apparently caused by a blunt knife. Police suspected that the wound

was self-inflicted and did not investigate the case further.

Elizabeth Jackson, a prostitute whose various body parts were

collected from the River Thames between May 31 and June 25, 1889. She was reportedly identified by scars she had had prior

to her disappearance and apparent murder.

Carrie Brown (nicknamed "Shakespeare", reportedly for quoting William Shakespeare's sonnets),

born c. 1835 and killed April 24, 1891, in Manhattan, New York City. She was strangled with clothing and then mutilated with

a knife. Her body was found with a large tear through her groin area and superficial cuts on her legs and back. No organs

were removed from the scene, though an ovary was found upon the bed. Whether it was purposely removed or unintentionally dislodged

during the mutilation is unknown. At the time, the murder was compared to those in Whitechapel though London police eventually

ruled out any connection.

Investigation

The investigation into the Whitechapel murders was initially

conducted by Whitechapel (H) Division C.I.D. headed by Detective Inspector Edmund Reid. After the Nichols murder, Detective

Inspectors Frederick Abberline, Henry Moore, and Walter Andrews were sent from Central Office at Scotland Yard to assist.

After the Eddowes murder, which occurred within the City of London, the City Police under Detective Inspector James McWilliam

were also engaged. However overall direction of the murder enquiries was confused and hampered by the fact that the newly

appointed head of the CID, Sir Robert Anderson, was on leave in Switzerland between September 7 and October 15, during which

time Chapman, Stride and Eddowes were killed. This prompted the Chief Commissioner of the Met, Sir Charles Warren, to appoint

Superintendent Donald Swanson to co-ordinate the enquiry from Scotland Yard. Swanson's notes on the case survive and are a

valuable record of the investigation.

Due, in part, to dissatisfaction with the police effort a group of volunteer citizens in London's East End

called the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee also patrolled the streets of London looking for suspicious characters, petitioned

the government to raise a reward for information about the killer, and hired private detectives to question witnesses separate

from the police. The committee was led by George Lusk in 1888. Albert Bachert, in 1889, claimed to be in charge of that group

or a similar group.

The Goulston Street Graffiti

After the "double event" of the early morning of September 30, police searched the area near the crime scenes

in an effort to locate a suspect, witnesses or evidence. At about 3:00 a.m., Constable Alfred Long discovered a bloodstained

scrap of cloth in the stairwell of a tenement on Goulston Street. The cloth was later confirmed as part of Eddowes' apron.

There was writing in white chalk on the wall above where the apron was found. Long reported that the graffiti

read:

"The Juwes are the men That Will not be Blamed for nothing."

Other police officers recalled a slightly different message:

"The Juwes are not The men That Will be Blamed for nothing."

Police Superintendent Thomas Arnold visited the scene and saw the graffiti. He feared that with daybreak

and the beginning of the day's business, the message would be widely seen and might exacerbate the general Anti-Semitic sentiments

of the populace. Since the Nichols murder, rumours had been circulating in the East End that the killings were the work of

a Jew dubbed "Leather Apron." Religious tensions were already high, and there had already been many near-riots. Arnold ordered

a man to be standing by with a sponge to erase the graffiti, while he consulted Metropolitan Police Commissioner Sir Charles

Warren. Covering the graffiti in order to allow time for a photographer to arrive was considered, but Arnold and Warren (who

personally attended the scene) considered this to be too dangerous, and Warren later stated he "considered it desirable to

obliterate the writing at once."

While the writing was found in Metropolitan Police territory, the apron was from a victim killed in the

City of London, which has a separate police service. Some officers disagreed with Arnold and Warren's decision, especially

those representing the City of London Police, who thought the graffiti constituted part of a crime scene and should at least

be photographed before being erased, but the message was wiped from the wall at approximately 5:30 a.m.

Most contemporary police concluded that the writing of the graffiti was a semi-literate attack on the area's

Jewish population. Author Martin Fido notes that the graffiti included double negatives, a common feature of Cockney speech.

He suggests that the graffiti might be translated into standard English as "The Jews are men who will not take responsibility

for anything" and that the message was written by someone who believed he or she had been wronged by one of the many Jewish

merchants or tradesmen in the area.

There is disagreement as to the importance of the graffiti in the Ripper case. Several possible explanations

have been suggested by various authors:

- Author Stephen Knight suggested that "Juwes" referred not to "Jews," but to Jubela, Jubelo and Jubelum,

the three killers of Hiram Abiff, a semi-legendary figure in Freemasonry, and furthermore, that the message was written by

the killer (or killers) as part of a Masonic plot (however, there is no evidence that anyone prior to Knight had ever referred

to those three figures by the term "Juwes")

- The murderer wrote the graffiti and then dropped the piece of apron to indicate a link

- The writing on the wall was already there and the murderer wanted to indicate a link in support of the

message.

- The message was already there and the murderer dropped the scrap coincidentally, without interest in making

a link (perhaps failing to notice the graffiti)

- The writing was added sometime after the apron piece was dropped, presumably shortly after the murder

(thought to have happened just before 1:45 a.m.), but before the discovery of the scrap of apron at 3 a.m.

Ripper letters

Over the course of the Ripper murders, the police and newspapers received many thousands of letters regarding

the case. Some were from well-intentioned persons offering advice for catching the killer. The vast majority of these were

deemed useless and subsequently ignored.

Perhaps more interesting were hundreds of letters which claimed to have been written by the killer himself.

The vast majority of such letters are considered hoaxes. Many experts contend that none of them are genuine, but of the ones

cited as perhaps genuine, either by period or modern authorities, three in particular are prominent:

The "Dear Boss" letter, dated September 25, postmarked and received September 27, 1888, by the Central News

Agency, was forwarded to Scotland Yard on September 29. Initially it was considered a hoax, but when Eddowes was found three

days after the letter's postmark with one ear partially cut off, the letter's promise to "clip the ladys ears off" gained

attention. Police published the letter on October 1, hoping someone would recognise the handwriting, but nothing came of this

effort. The name "Jack the Ripper" was first used in this letter and gained worldwide notoriety after its publication. Most

of the letters that followed copied the tone of this one. After the murders, police officials contended the letter had been

a hoax by a local journalist.

The "Saucy Jack" postcard, postmarked and received October 1, 1888, by the Central News Agency, had handwriting similar

to the "Dear Boss" letter. It mentions that two victims — Stride and Eddowes — were killed very close to one another:

"double event this time." It has been argued that the letter was mailed before the murders were publicised, making it unlikely

that a crank would have such knowledge of the crime, though it was postmarked more than 24 hours after the killings took place,

long after details were known by journalists and residents of the area. Police officials later claimed to have identified

a specific journalist as the author of both this message and the earlier "Dear Boss" letter.

The "From Hell" letter, also known as the "Lusk letter," postmarked October 15 and received by George Lusk of the Whitechapel

Vigilance Committee on October 16, 1888. Lusk opened a small box to discover half a human kidney, later said by a doctor to

have been preserved in "spirits of wine" (ethanol). One of Eddowes' kidneys had been removed by the killer. The writer claimed

that he had "fried and ate" the missing kidney half. There is some disagreement over the kidney: some contend it had belonged

to Eddowes, while others argue it was "a macabre practical joke, and no more."

Some sources list another letter, dated September 17, 1888, as the first message to use the Jack the Ripper

name. Most experts believe this was a modern fake inserted into police records in the 20th century, long after the killings

took place. They note that the letter has neither an official police stamp verifying the date it was received nor the initials

of the investigator who would have examined it if it were ever considered as potential evidence. It is also not mentioned

in any surviving police document of the time.

Ongoing DNA tests on the still existing letters have yet to yield conclusive results.

Modern perspectives

Investigative techniques and awareness have progressed greatly since 1888. Many valuable forensic science

techniques taken for granted today were unknown to the Victorian-era Metropolitan Police. The value of interpreting motives

of serial killers, the concept of criminal profiling, fingerprinting, and other such knowledge and intelligence that have

developed were poorly understood if not altogether unknown. Whilst the investigation was not nearly as sophisticated as police

work is today, the detectives' inquiry included interviewing witnesses and residents of the area, following up tips from the

public, and other standard police procedures. Common modern forensic investigation methods such as fingerprinting, DNA analysis

and blood typing had not yet been developed.

Media

The Ripper murders mark an important watershed in modern British life. Whilst not the first serial killer,

Jack the Ripper's case was the first to create a worldwide media frenzy. Reforms to the Stamp Act in 1855 had enabled the

publication of inexpensive newspapers with wider circulation. These mushroomed later in the Victorian era to include mass-circulation

newspapers as cheap as a halfpenny, along with popular magazines such as the Illustrated Police News, making the Ripper the

beneficiary of previously unparalleled publicity. This, combined with the fact that no one was ever convicted of the murders,

created a legend that cast a shadow over later serial killers.

Some believe that the killer's nickname was invented by newspapermen to make for a more interesting story

that could sell more papers. This became standard media practice with examples such as the Boston Strangler, the Green River

Killer, the Axeman of New Orleans, the Beltway Sniper, and the Hillside Strangler, besides the derivative Yorkshire Ripper

almost a hundred years later and the unnamed perpetrator of the "Thames Nude Murders" of the 1960s, whom the press dubbed

Jack the Stripper.

The poor of the East End had long been ignored by affluent society, but the nature of the murders and of

the victims forcibly drew attention to their living conditions. This attention enabled social reformers of the time to finally

gain the support of the "respectable classes." A letter from George Bernard Shaw to the Star newspaper commented sarcastically

on these sudden concerns of the press:

"Whilst we Social Democrats were wasting our time on education, agitation and organization, some independent

genius has taken the matter in hand, and by simply murdering and disembowelling four women, converted the proprietary press

to an inept sort of communism."

|

|

|